Live From El Salvador!

Live from El Salvador!

We’ve been in El Salvador for the last week, visiting the farms owned by the Menendez family of Ahuachapán, so it seemed like a good time to send out an update and some pictures.

Our team arrived in San Salvador on the 27th and were met at the airport by Roberto, one of the many people employed by the Menendez family. He took us to Casa Mia, a charming bed and breakfast in the heart of San Salvador. After dinner at Cadejo Brewery (a local microbrewery) we turned in for the night in anticipation of heading to the farms in the morning.

In the morning we were picked up by Gullermo and Miguel Menendez, the son’s of the family patriarch Miguel Menendez, Sr. From San Salvador we drove 1.5 hours west, to the city of Ahuachapan in the Sierra Apaneca-Ilamatapec. This volcanic mountain range extends to the east from the border with Guatemala, encompassing some of El Salvador’s best coffee growing terroir. The Menendez family has been operating coffee farms in these mountains since the 1850′s, with Miguel Sr representing the third generation of coffee farmers in the family.

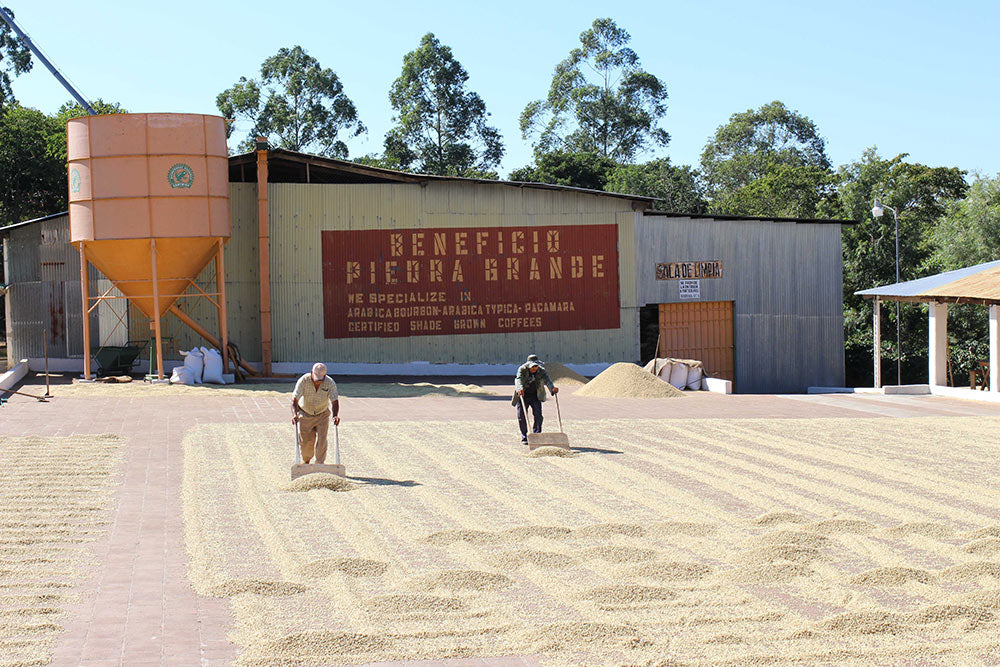

Our first stop was the family’s coffee mill, Beneficio Piedra Grande. The Engineer (agronomist and lead cupper) had set up several tables of coffee from the family’s farms for us to taste. By the time we had finished, the workers were bringing in the days harvest, giving us a chance to watch the wet mill in action.

In establishing Beneficio Piedra Grande, Miguel Menendez Sr separated himself from much of the rest of the coffee farmers of El Salvador. For the most part, very few coffee farmers operate a mill for processing the ripe fruit. Instead, cherry is taken to one of the large mills owned by the exporting companies. There the coffee from an individual farm is often lost in the shuffle, getting mixed in with coffee from many other farms. Building the Beneficio allowed Miguel to promote the coffee from his own farms and showcase the quality of what he was growing.

We started the following day by visiting Finca Buena Vista, a farm we’ve been purchasing coffee from for the last four years. On the road up to the farm we passed farms owned by the Menendez’s neighbors, the vast majority of which were showing signs of the current Roya (coffee leaf rust) outbreak that is rampaging through Central America. Roya is a fungus that grows on the leaves of the coffee plant, causing devastation to coffee crops wherever it emerges.

For the last several years Roya has been wreaking havoc on the coffee farms of Central America, including El Salvador. On the roads of the Apaneca-Ilamatapec range we saw the full effects of the outbreak. Almost every farm we saw was heavily denuded by the disease. Only a few leaves remained on the coffee plants, evidence of a harvest almost completely lost. Many farms had been abandoned. With no coffee to harvest, many farmers can’t afford to pay workers to trim back the forest, and in as little as two years the already weakened coffee plants can be overwhelmed. In many cases these abandoned farms were indistinguishable from the surrounding forest.

Coffee farmers have two main choices when it comes to fighting Roya. The most common is to plant coffee varieties that are resistant to Roya. Many of these are hybrids of Arabica and Robusta bred to be disease resistant and higher yielding. The downside to this option is that the quality of the cup is often significantly reduced. Additionally the current Roya outbreak seems to be mutating extremely quickly and it is feared that varieties that are currently resistant to Roya won’t be so for much longer.

The second option is the one that Sr. Menendez has opted to take. Several times throughout the year coffee farms are sprayed with fungicides designed to stop the spread of the disease. Traditionally topical applications of copper sulfate were enough to control the spread of Roya, but the current outbreak seems to be resistant to these methods. Commercial fungicides made by agrochemical companies like Syngenta and Bayer seem to be the only sure way to control the infestation. Unfortunately these methods are extremely expensive. Farmers like the Menendez family not only have to pay for these expensive chemicals, but they also require huge amounts of labor to apply, as each plant has to be individually sprayed. With hundreds of thousands of plants per farm, and nine farms to spray this is a pricey option for the Menendez family, but it is the only one that ensures the quality that their customers have come to expect.

After hiking Buena Vista with Miguel Sr, Miguel Jr, and Guillermo we returned to Piedra Grande to cup more coffees with the engineer. Among the coffees on the table were the first of the year’s crop of Pacamara variety. Despite the reduced harvest due to Roya the quality of this year’s cups is extremely high, especially in the Pacamaras. This variety was developed in El Salvador, a cross between Pacas (a smaller Bourbon) and Maragogype (a giant Typica). Compared to its Bourbon cousins Pacamara is lower yielding and more susceptible to Roya, but in the cup it can be simply amazing. Notes of tropical fruit pop out with an intense sweetness that is complimented by a delightfully juicy acidity. It is a variety that perfectly suits the ideology of the Menendez family’s top tier farms; quality over quantity.

In the afternoon we traveled to Finca El Rosario, a farm owned by the Menendez family near the city of Ataco. it sits in the flat area between two volcanoes, on the crest of the Apaneca-Ilamatapec range. In 2005 the Ilamatapec volcano erupted, covering El Rosario in a layer of ash. In the short term this nearly destroyed the farm. Ash covered the coffee plants, and when mixed with rain it formed a thick paste on the leaves, removing their ability to convert sunlight into energy for the plants, killing them. In the long term the ash proved to be a boon to the farm, greatly enhancing the soil with the nutrients that coffee loves.

Today El Rosario feels almost more like an English garden than a coffee farm. At the crest of the mountain range the farm is exposed to high winds that can devastate the coffee plants. To combat this the Menendez family has planted over 17km of trees to act as windbreaks. They criss cross the farm dividing it into orderly segments of a few hundred square feet. Each of these is carefully tended, and allows for experimentation in controlled areas. This is where the Menendez family tries out new varieties, including a new one that tastes almost like the syrup from canned peaches. Only 20 pounds were produced this year, but with more plants coming into production it should be ready for export within the next two years.

On our final day we visited Finca Las Delicias. This farm sits on the north slope of Cerro Las Ranas, a dormant volcano in the Apaneca-Ilamatapec range. Coffee is planted up to 1650 meters, with the remaining 250 meters of the mountain covered in native forest. In the caldera at a top sits a lake teeming with frogs, giving the mountain its name. The Menendez family has planted these steep slopes with several lots of Pacamara and Bourbon plants. The top of this farm represents the upper limit of where coffee can grow in El Salvador, and these extreme heights produce some of the family’s highest scoring coffees.

After spending a week with the Menendez family it is readily apparent why their coffees are some of the best in El Salvador. They spare no expense in ensuring that their coffees taste as good as possible. We haven’t decided exactly which coffees will be heading to Water Avenue this year, but we expect them to arrive in the early parts of the summer. Over the next few days we’ll be meeting with Cuatro M Cafes, who own Finca El Manzano, a farm we are also privileged to work with.